Seven Days In Tibet

A view toward the Himalayas peeks through multitudes of prayer flags.

China was genuinely wonderful - I was smitten with all of it, even the moments that might seem unpleasant on the surface. But just a smidgen of a trip through Tibet complicated and soured my feelings about China. Let's start with Lhasa:

The old town of Lhasa where Tibetan culture thrives is deeply atmospheric: women wear traditional dresses, Buddhists in prayer seem to outnumber any other pedestrians or street vendors, narrow stone streets thread between centuries-old Tibetan style buildings, creating alleys and alcoves that you could explore for days. in the enter of old town, you see a steady flow of Buddhist "pilgrims" (our guide called them) practicing the kora: a meditative prayer that's done while walking in a large circle around sacred places. The kora in Lhasa is a circular pedestrian street that passes several sacred monuments with the main temple at the center. As they walk the kora clockwise, people also chant and often holding small prayer wheels and spinning large fixed prayer wheels as they walk by rows of them. Some people prostrate themselves as they travel the kora - first kneeling, then laying flat in prayer and then rising and stepping forward to repeat the yoga-like flow of movements. A strong, noticeable tide of worshippers walks the kora at almost any time of day.

Evening: people walking the kora in Lhasa, including two monks and a man kneeling in prostration.

What does this have to do with China?

Marching in the opposite direction, counter-clockwise, on the kora circuit are Chinese police, SWAT teams and military personnel making their presence known. They are not a constant parade like the pilgrims are, but they are impossible to miss: they usually march in 10-man formations (at least, I never saw a woman among their ranks) and wear Kevlar vests, helmets - some with face masks - and carry semi-automatic rifles and riot shields. Some teams carry fire extinguishers, to prevent or end any protestor's attempt at self-immolation.

Just to enter this circular street through old Lhasa, everyone must pass through a police checkpoint; all bags are x-rayed, but white people were waved through without an ID check.

Worshippers throw incense into the stupa as they pass by on the kora in Lhasa.

Adjacent to this old neighborhood, a broad modern boulevard that leads to "Liberation Square" is decorated with Chinese flags. Three massive black police vehicles were parked here at the edge of old town -- one the size of a motorhome, another sort of resembling a tank, all three bristling with communications antennae and uniformed personnel with weapons. One officer carrying a powerful-looking rifle smiled at me and called, "Hello!" in English. Incongruous.

Liberation Square, Lhasa.

Attempt to photograph any police or military presence - or accidentally capture it in a photo - and you'll be pulled aside by a handful of officers and made to go through all your photos, presumably to delete the offending images.

Outside Lhasa, checkpoints were frequent. Our tour spent three long days driving across western Tibet from Lhasa to the Himalayas - nearly the border of Nepal. Along the way we became accustomed to our microbus stopping and our guide telling us to get out our passports.

About Liberation: this is the Chinese government's term of art for its annexation of Tibet in 1950, a situation that Tibet's exiled Dalai Lama described as cultural genocide.

I noticed portraits of Chinese leaders and Chinese flags prominently displayed everywhere I went in Tibet, including in restaurants and the one private home our tour group visited.

(Admittedly, all the areas we visited are frequented by tourists, whose admission to the region is tightly controlled by the Chinese government; we saw what they wanted us to see).

"Cultural relics protections, everyone's responsibility" reads an ironic sign at Tashi Luhnpo monastery in Shigatse, Tibet. #culturalrevolution

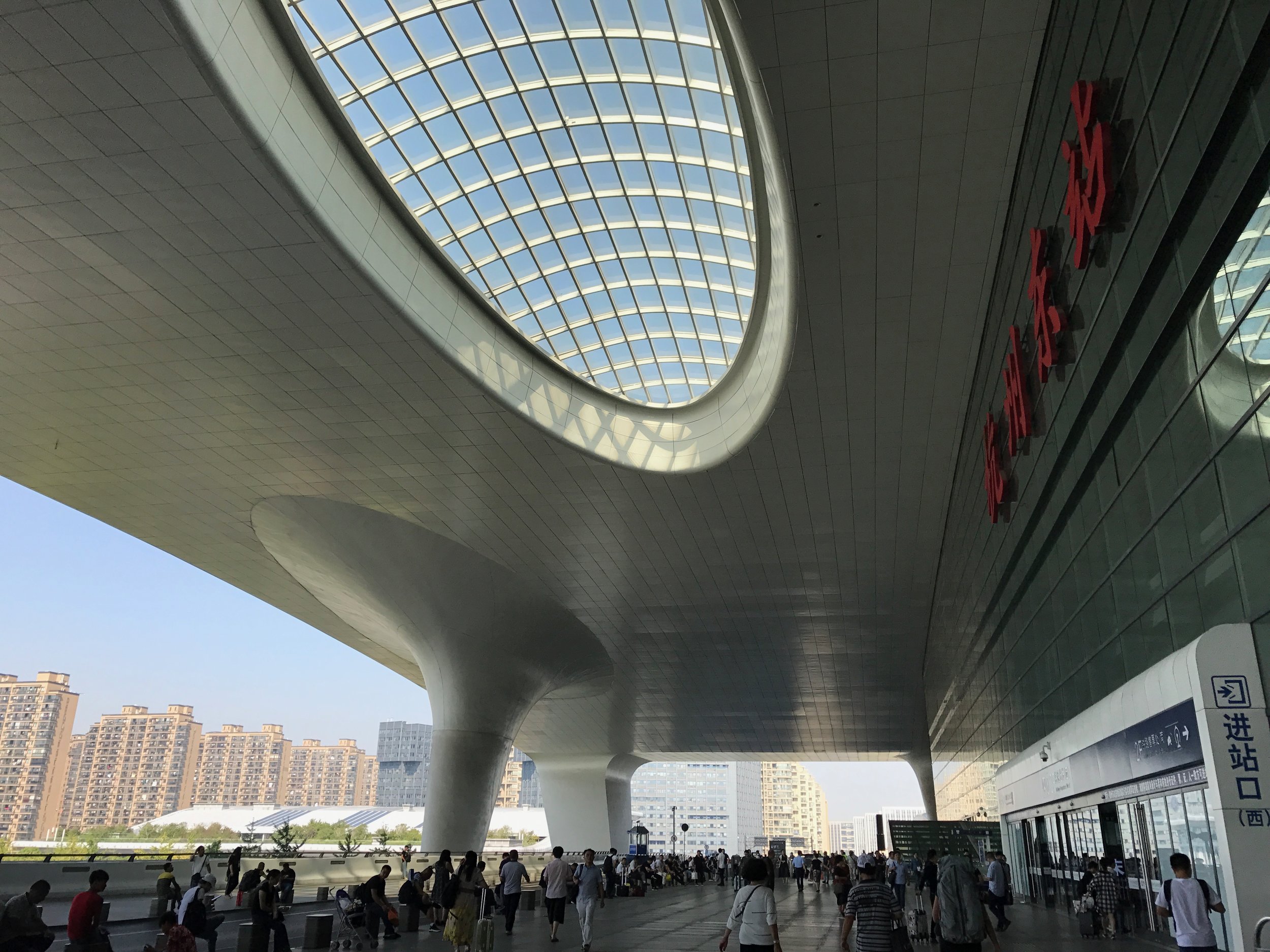

Chinese transportation projects and development projects in Tibet are double-edged sword. Arguably, they raise the standard of living but at the expense of traditional customs, culture and religion. Old-stye Tibetan homes are razed to make way for apartment buildings that elderly Tibetans don't want to live in, we were told. The same road and rail projects that might boost the Tibetan economy also speed the cultural disintegration that results from scores of Chinese and others easily moving in to confer and confirm their own cultural stamp on Tibet.

Living room of a traditional Tibetan family's home, complete with Chinese leaders' portraits.

"Ask my anything, but maybe don't lead with politics," our guide Tensing told us, smiling, early on our tour. Guided tours with registered agencies and credentialed guides are currently the only way to visit Tibet. Tensing was a font of information on Tibetan Buddhism and culture, but only on rare occasion referenced Liberation, the Cultural Revolution or the politics of Tibet's lack of sovereignty.

My visit to Tibet was brief and I saw an extremely narrow slice of life and geography, and it was through my Western perspective without benefit of deep knowledge. But I left feeling both concerned for the vitality of Tibetan culture, and also resigned that perhaps the tipping point of Chinese appropriation has already passed.

[Tibet tour: October 2-9, 2017]