Radio Free Benin

When you are a radio pro on a tour of a radio station and the director of a live show asks you, “Want to go on the air?” The answer can only be, “Absolutely!”

Ocean FM is owned by the same Cotonou, Benin, media group that publishes a major newspaper here, Le Matinal. The offer of a tour sprang from a talk I gave earlier in the week; I had hoped I might be able to visit a local radio station, and a few days later I was standing with the managing editor of Ocean FM in their control room, on the guest end of a spontaneous booking process.

A public affairs officer from the US Embassy here had arranged my visit to Ocean FM and she balanced my "yes, obviously" with a hesitant, "ok but...." The co-hosts would ask me questions in English, and presumably interpret some of the conversation into French. The PAO didn't want to be on the air and she sat away from a mic went we got into the studio. But the free-wheeling nature of the show didn't conform to those subtleties and sooner than later the host was lobbing her questions, too.

I don't speak French or any of the several local languages in Benin, but I do speak control room, and it felt great to hang out here.

Ocean FM isn't exactly a morning zoo format but it was loose enough that the host riffs unscripted on the news of the day, takes listener calls and is clearly comfortable spending a few minutes with impromptu guests who weren't pre-interviewed. Three topics emerged from their questions to me: What do you think of our radio station? How can our journalists get training in the U.S.? Why is radio important?

The second question is a variation on a theme that I encounter frequently, and it stabs me in the heart a little every time. It lays bare the truth that opportunities aren't equally distributed; that people in developing countries are rightfully ambitious and unflinching in seeking advancement; it belies the curiosity that people are still keenly interested in coming to America, even though some parts of America clearly aren't interested in welcoming them; and for me, it stirs up a nest of unresolved feelings about how the place of your birth sets a course of fortune or misfortune that can be hard to disrupt, and why some people are born with the luck of geography and others aren't.

"How can we come to the U.S.?"

My thoughts on this are so tangled that I can feel my chest fill with emotion, and yet my answer in careful English is entirely anodyne and superficial. "I know there are training programs that exist for journalists, and I'm sorry I don't have details about them." Ugh. Pathetic dodge.

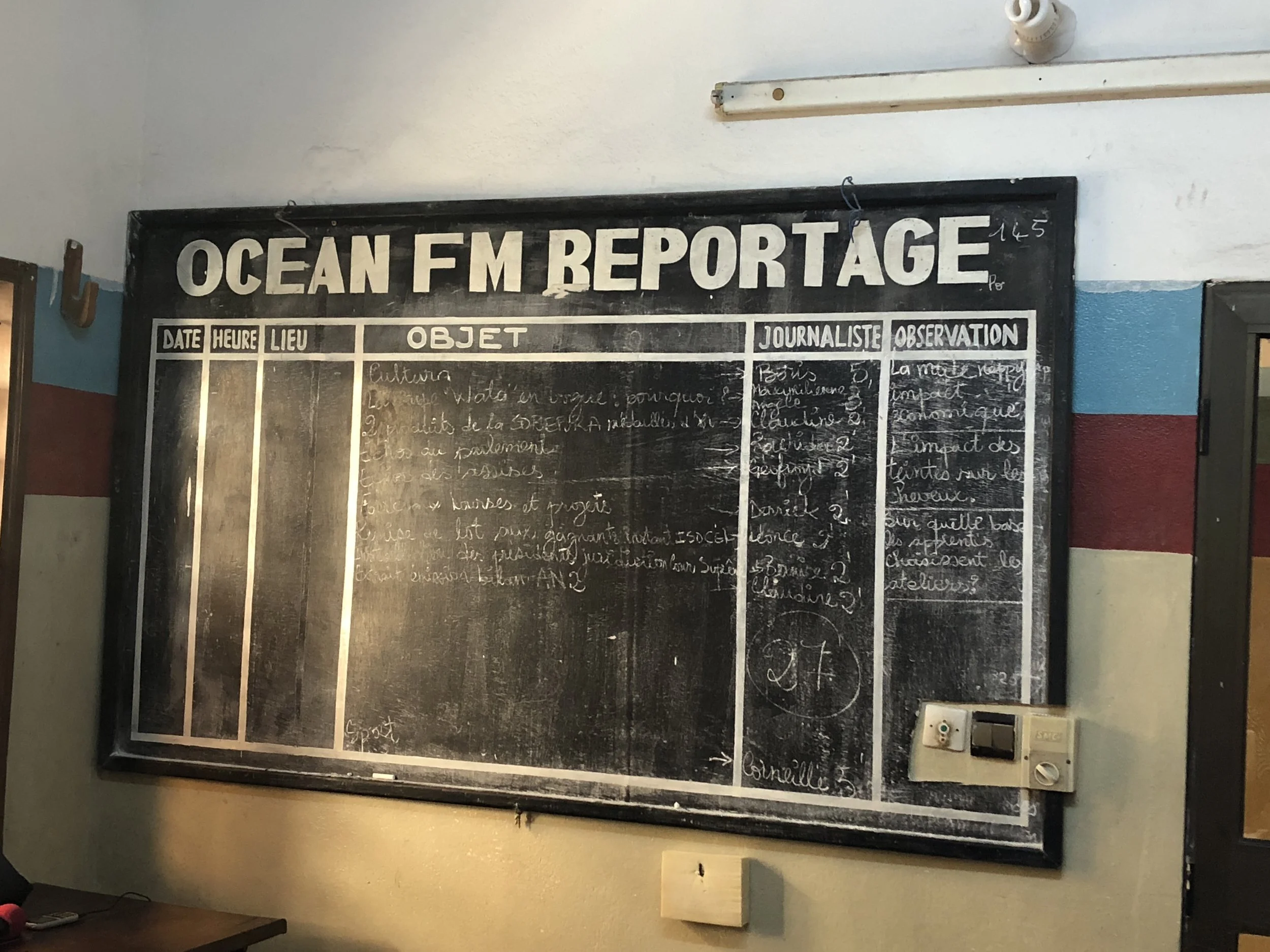

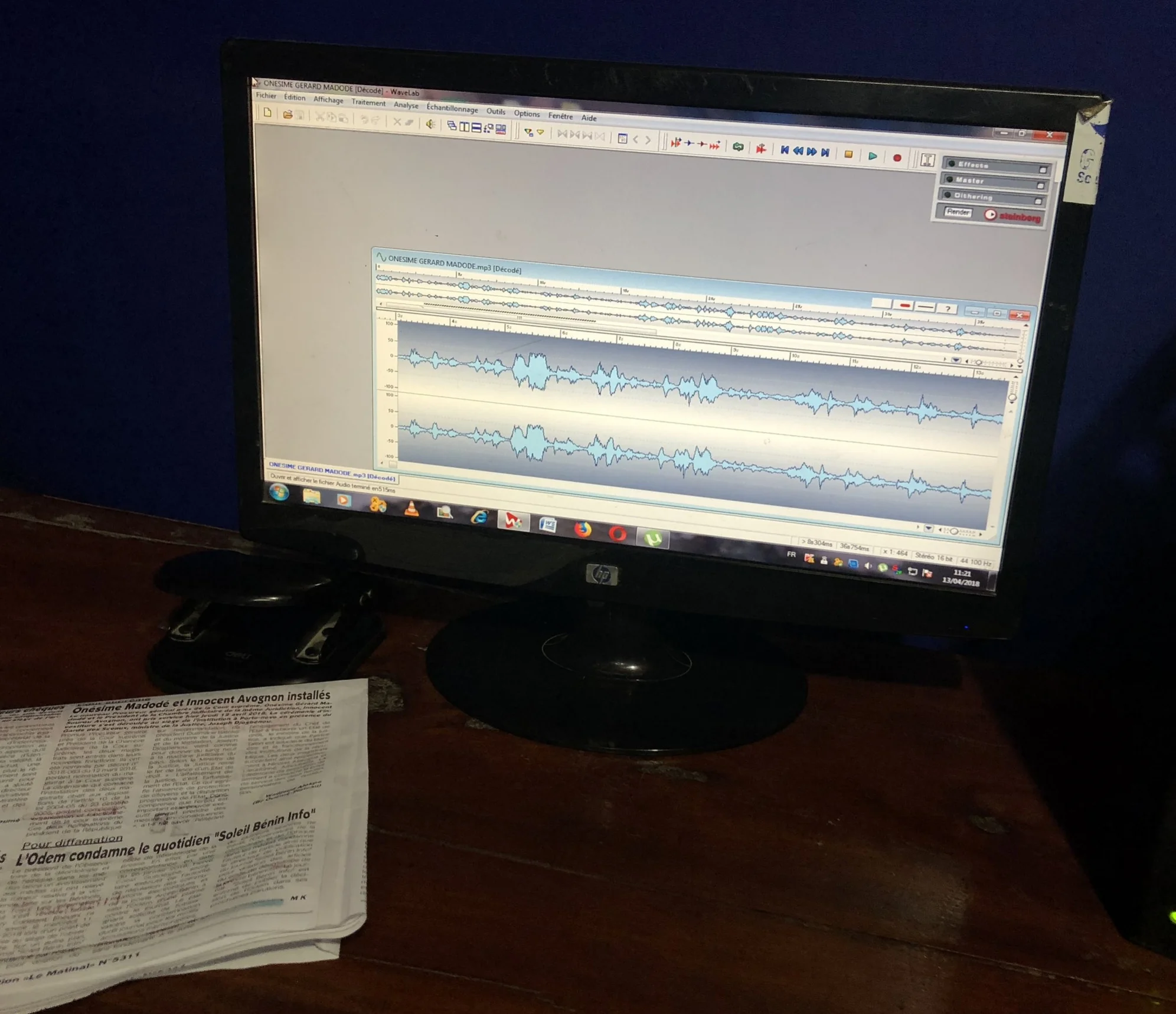

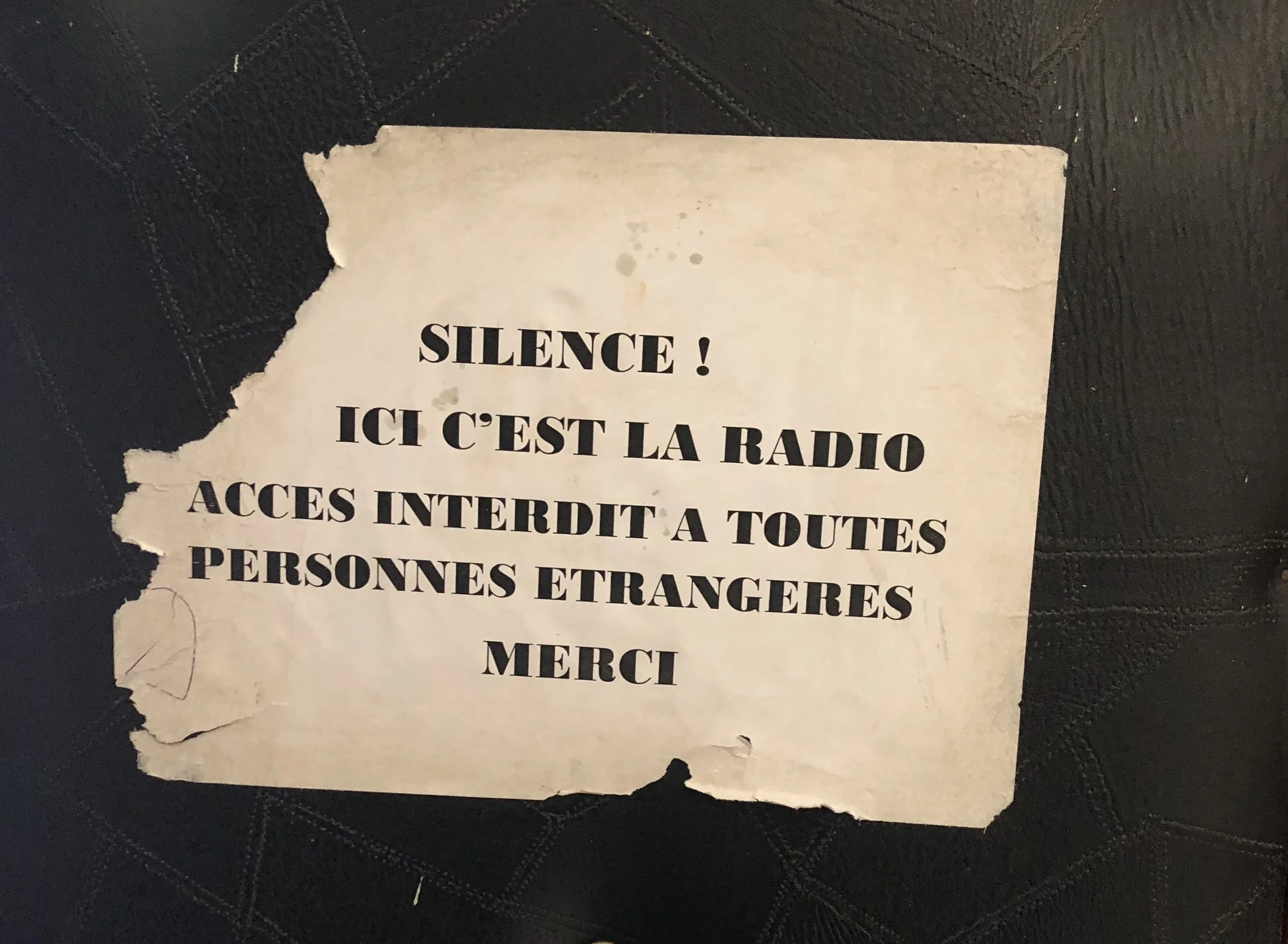

I was on more comfortable ground with their other lines of questioning. So much of the equipment and setup of Ocean FM was familiar. The studio mics, the desktop editing software, the mixing boards -- you'd find versions of this equipment (maybe slightly newer) in most radio stations in the U.S. One small workroom had tables around its perimeter with computers and mixers where reporters and producers wrote and mixed their stories. The larger workroom had a large common table at its center, but everyone's attention was oriented to the assignment board that filled one wall. In the workrooms, lazy ceiling fans half-heartedly dispersed the heat and humidity, but the studio and control room were noticeably cooler, preserving the temperature-sensitive equipment.

I do love an organized assignment board!

Why is radio important? In America, my answer would resemble a lot of what you hear people like me tell you during public radio pledge drives. But my brief introduction to Benin led me to this conclusion: education levels are low and poverty is high, but Benin is still one of the most stable republics in West Africa. This is exactly the kind of place where reliable, solidly reported news on the radio can make an important impact on how citizens relate to their government and their communities. Good radio is democratizing: you do not need wealth to hear it, you do not need literacy to learn from it and it can reach nearly everywhere.

[April 2018.]