Journalism Reality Check

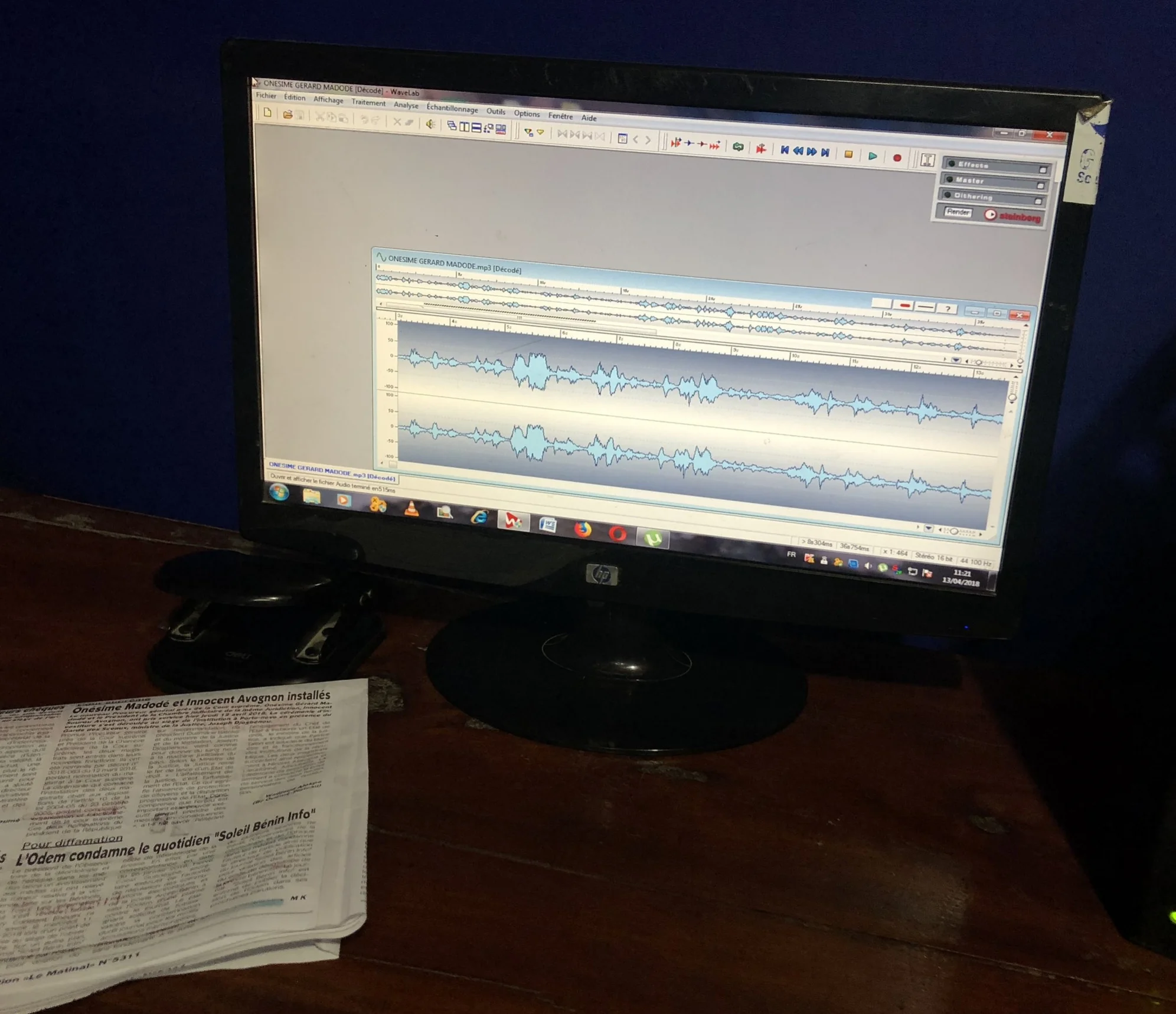

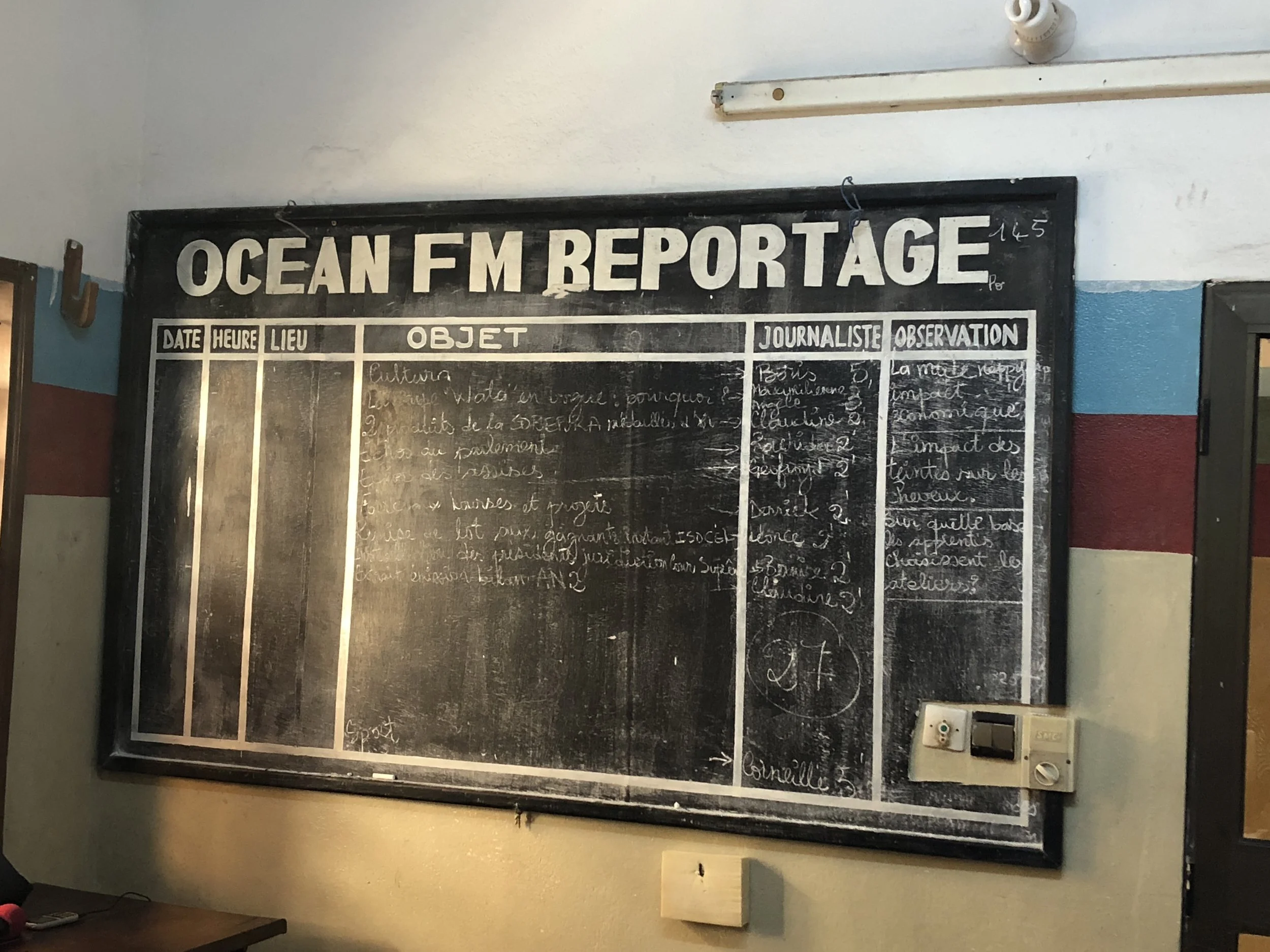

The managing editor of Ocean FM, in her radio station's control room.

"Everyone listens to you, everyone knows who you are, but you don't make any money." This was how one radio journalist characterized her father's lament that his smart, talented daughter insisted on being a radio reporter.

The U.S. Embassy in Cotonou, Benin, invited five Beninois women journalists to a roundtable discussion with me about what it's like to be in our profession, and what we can learn from each other. The pretense of these setups always worries me — that I have indispensable wisdom to impart, or that the strategies and tactics I've learned in the U.S. will be applicable to their circumstances.

A report by Freedom House describes Benin's press freedom as not great, but better than its neighbors. The problem of access journalism — the ability of reporters to directly question and get honest answers from people in power — is familiar, but the consequences here are more dire. In America, over reliance on access can lead to stories that lack important critique or stories that curry favor with the very politicians who should be covered critically. Here, critical reporting might lead to the government shutting down your newspaper for a period of time, as happened to the major publication Le Matinal.

The confluence of social media and “fake news” is also creating problems for news media here, which these women described with grim expressions. The encrypted messaging service WhatsApp is used widely in Benin, often with large distribution lists circulating dubious information. On the one hand, accurate information can spread so easily and quickly that it leaves journalists wondering what their own role is in distributing information; on the opposite hand there have been numerous fictitious stories that spread on WhatsApp, and that then were repeated in mainstream media by poorly skilled reporters who didn’t ground truth the story.

And then there is the problem of per diems. This isn’t unique to journalism, many people in Benin are not paid salaries but instead receive per diem payment for work. For reporters, it means someone is paying you to report a specific story, or not report it. (The Freedom House report names this what it is: bribery.) It puts reporters in the position of getting paid, or not getting paid, in dubious circumstances.

On the surface, many of the problems they face would make their American female colleagues nod in solidarity. Dealing with squirrelly politicians. The metastasis of fake news. Low pay. I listened and took notes as they spoke through an interpreter about their specific experiences with these problems, and it left me feeling like.... wow, do we (Americans) have no idea what our colleagues are facing around the world, even in relatively good circumstances.

And then there is sexism.

Their stories unfolded gradually, their trust in each other growing the longer we spent together. One woman would obliquely refer to the sexism she faces being one of the few women working as a political reporter, and everyone would nod. The next woman would add a little detail, noting that women reporters were passed over for the plum assignment to cover the opening of the parliament that week. By the end of the discussion, one woman had explained that men would sometimes demand sex in exchange for giving her an interview, an anecdote that elicited entirely too little reaction from her peers. They hadn’t had these conversations among themselves before, and they hadn’t yet found support and solidarity with women working in competing newsrooms. Yet they bonded in the shared frustration of trying to pursue their work in an ecosystem that wasn’t built to to honor their integrity.

As they talked, I was thinking of the countless hours I've spent reading and discussing the #metoo stories that eviscerated U.S. newsrooms and shattered journalists' trust in their own institutions. The response to those stories was outrage, and that demonstrates the difference between what U.S. journalists are dealing with and what faces these colleagues in Benin. Meanwhile, I was also internally cataloging the minor grievances and petty rivalries that can preoccupy a break room or give rise to secret Slack channels back home, and I was feeling ill over how those slights compare to the egregious circumstances these women matter-of-factly described. And even as I counseled myself that it's unproductive to compare indignities, I knew in the back of my mind that I am lucky for the things I have to complain about.

Five of Cotonou's journalists explained to two Americans what it's like to do their work in Benin, but still had energy to smile afterward.

[April 2018]